Another movies write-up on this episode of Fiat Benelux. I’ve been watching movies lately!

The Bikeriders had my rapt attention all the way through. Each of the characters pulled me right in. Especially Zipco, portrayed by the great Michael Shannon, who brooded convincingly about how he wished the world were more violent than it is. But my emotional investment was not to be repaid.

I expected more motorcycle chases in this movie, and not so much dithering and boozing. But that’s the tension of the whole thing: the Vandals are really just a weakly-allied group of violent rascals. They’re not really committed to their bikes, their fellows, or to anything else. During a moment of surprising retaliatory violence, a key character turns to the leader and asks “Is that all this club is?”

The question goes unanswered because of course the Vandals aren’t about anything. The guy who asks (Austin Butler) is the same one who rode his bike through a bunch of stoplights till it ran out of gas then waited, chuckling, for his imminent arrest.

I respect the honesty of this depiction. It would have been romantic to see passionate commitment flowing out of these brigands, but of course that would have been unrealistic. Instead they drift through the world, encountering conflict haphazardly and meting out revenge ad hoc.

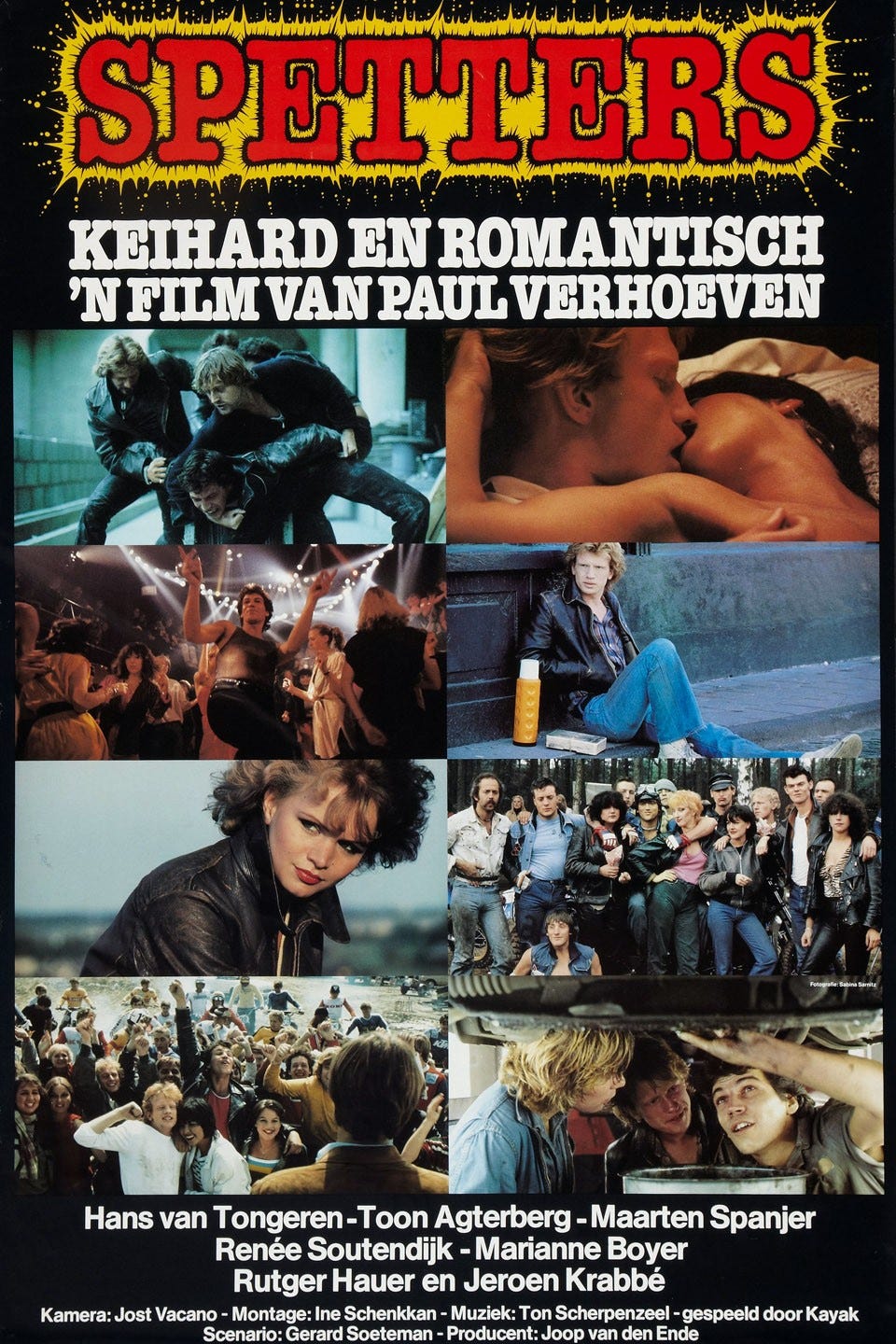

Another movie about two-wheelers offers more insight into a milieu, a generation, a nation. If The Bikeriders are torn apart by their own nihilism, then the three reckless youths from Paul Verhoeven’s Spetters are torn apart by the Netherlands itself.

Most often compared to Saturday Night Fever (a disco scene makes the link explicit), Spetters is also a kind of Dutch precursor to the greatest of all ‘80s teen dramas, River’s Edge. Eef, Hans and Rien commit themselves totally to the vroom-vroom, with church, career and babes at the far periphery of their thoughts. As in River’s Edge, the moral bankruptcy of the adult world underscores the questionable judgment of the youths. It’s filmed in Maassluis, outside Rotterdam, where the great rivers of western Europe sludge their way into the sea.

Verhoeven depicts the inherent cruelty of generational turnover. In the first scene, Eef is trapped on a motorbike behind his father, who rides a tractor on a dirt lane near a greenhouse. Eef is made to wait until a they reach a fork before he can speed past his dad. Later, in a ritual that strangely recalls their family’s Christianity, this same father brutally beats Eef.

Other corrupt elders include Witkamp (Rutger Hauer), the motocross champion that the boys venerate. With the assistance of TV anchorman Frans Henkhof (Jeroen Krabbé), Witkamp repays their worship with scorn and humiliation. Henkhof intones platitudes about how “the youth is the future,” and then cheerfully participates in the exploitation of that youth.

Spetters gave me my action fix but Verhoeven has a knack for cutting his exhilaration with a profound sense of futility. Zeal for motorbike-riding is, after all, a juvenile impulse towards speed, an utterly bereft sensuality that’s taking over the Old World. Jesus replaced by TV, farming replaced by high-speed trains.

It’s the kind of movie where you know a girl’s thoughts run towards family-making because she wanders past a curtainless window and sighs at a pregnant woman checking out baby clothes. Fientje, that pretty window-looker, is a wiser operator than any of her male consorts, but these boy-men seem to circumscribe all of her paths forward. Just as the male characters are oppressed by their forebears, she barely registers as a character, subsumed as she is by toxic masculinity.

The homoeroticism is not stylish and suggestive, as in The Bikeriders. Instead it’s lurid and apocalyptic in the Verhoeven style. A chortling gang of gay guys throw food at a vendor and then get boiling french-fry oil dumped on them. Eef stalks two men to their underground tryst, watching them from a train track under construction, a primitive hunting scene playing out under fluorescent light and concrete.

After his crash, Rien’s electric wheelchair is a poor substitute for a motorbike, but good for a laugh from the overbearing crowd of well-wishers. This carnival of sentimentality may be the key scene of Spetters: a false redemption, a false camaraderie, and a giggling crowd-energy that dissipates as quickly as it gathers.

Eef’s homosexuality, Rien’s paralysis, and Hans’s job rebuilding a destroyed bar all sync up: these are the punishments for their having dared to exist. Hans gets the girl but there’s still a punitive feeling at the end of Spetters. The dreams of motocross glory are crushed by a laughing crowd of bar patrons.

The aggressive carelessness that pervades Spetters was just a warmup for Verhoeven’s move to Hollywood, where he would become infamous for the giggling depravity of RoboCop, Total Recall and Basic Instinct. In a tribute to Starship Troopers, David Roth nails it:

It has become clear, in these last decades of decadence, decline, towering institutional violence, and rampant bad taste, that American life is stuck somewhere inside the Paul Verhoeven cinematic universe.

Before revealing America’s appetite for spectacles of cruelty, Verhoeven did the same for his native country. While the Netherlands looks on its surface to be an exemplar of postwar technocratic rationality, Verhoeven appreciates the seething rage beneath.